What happened when I decided to read a book by my mother’s literary love

My mother was the source of all stories for me. She told me stories. She read me books. When she got bored of reading me my favorites, she’d add silly details, mix the story up, and get me to laugh hysterically.

I love stories because of her. Reading them and writing them.

At 83, my mother still hangs on, three years after she was first put on hospice and given ten days to live. In the last stages of vascular dementia, she is confined to a hospital bed in the family room. She sometimes smiles, but usually I barely see her eyes behind her eyelids. She speaks only a few words, which have all the right sounds and inflections, but make no sense.

I reach for her hand, because then she turns her head to me. I tell her about my students and what we’re reading. I am a high school English teacher now, like she used to be years ago. I want to share these things with her. I don’t know if she hears or understands anything I say.

This month I made it my mission to read a book by her favorite author, William Faulkner. Maybe it’s because I can’t know what’s in her head now. I want to understand what she thought about, what used to be important to her.

Years ago, with a look in her eyes of distant remembrance, she told me: Nobody writes like Faulkner.

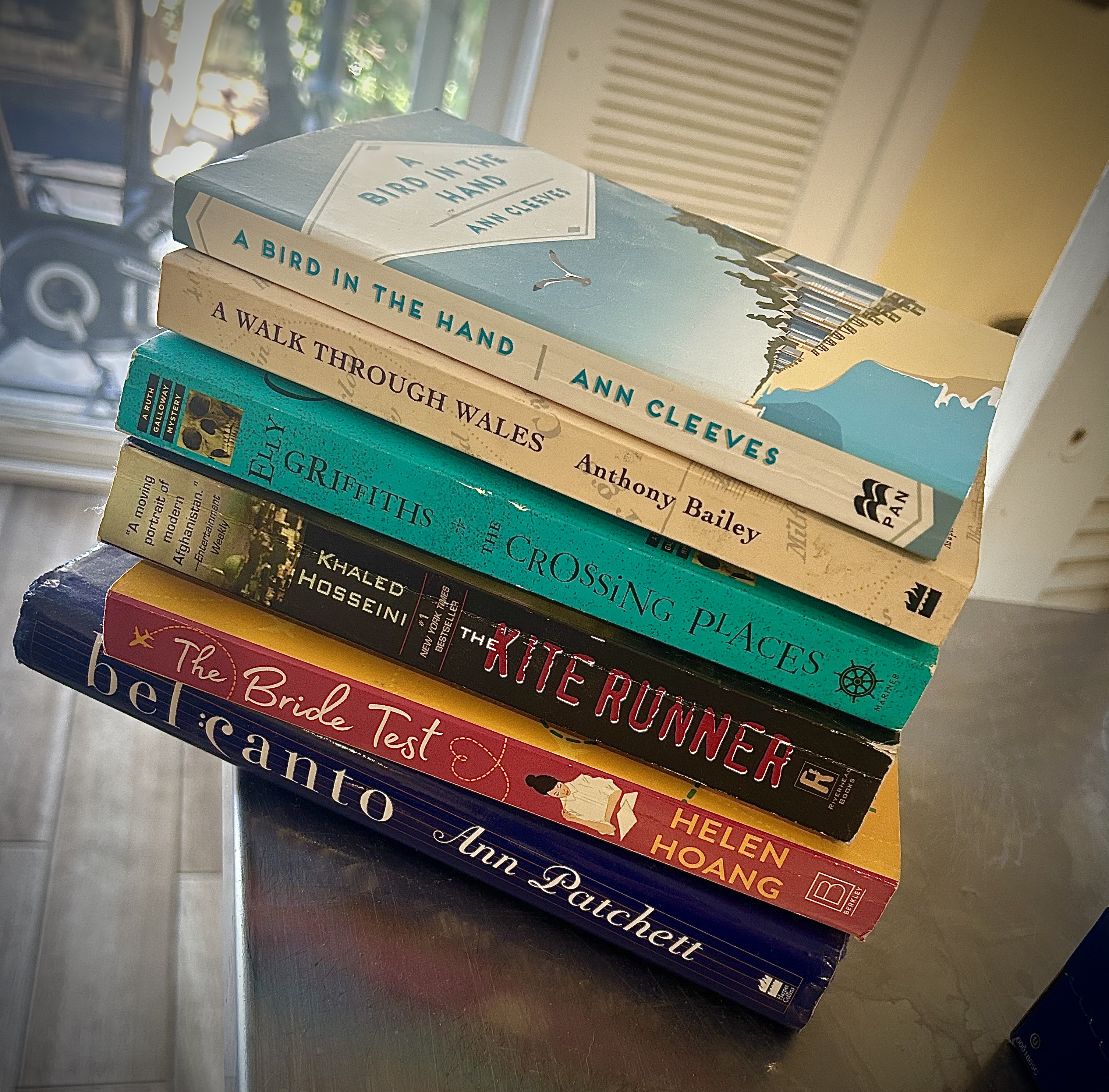

This month I got my hands on a copy of Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom. A book that has been compared to James Joyce’s Ulysses, for its complexity and the way it breaks the rules. Not an easy read. Some sentences are just strings of adjectives. The narrative often switches abruptly to a part of the story mentioned earlier.

To understand everything, I had to read chapter summaries in Spark Notes. And look up the meanings of words I’d never heard before. Suppuration, anybody? (It means the fluid produced by an inflammation.)

I’m a quick reader, but it took me a week to forge my way through the muddy wilds of Absalom Absalom.

My mom is not a southerner like Faulkner, but she loved the way he told a story. Absalom is told in an unconventional way: by multiple narrators, most of whom can’t be trusted. Like an impressionist painter, Faulkner paints layer upon layer, filling in the outlines of events again and again, making the picture deeper and sadder each time.

The book reads like a mystery, even though the first chapter tells the novel’s entire plot. Thomas Sutpen—a man who grew up poor in Virginia—comes back to the south from Haiti in the 1840s to build a mansion on a hundred acres of mud in Mississippi. He gets rid of his Haitian wife, along with his first son, when he finds out she is part African. He marries the daughter of a local merchant, to get some instant middle class respectability. It’s all part of The Design, the plan he set in motion when he left rural Virginia.

The book reads like a mystery, even though the first chapter tells the novel’s entire plot. Thomas Sutpen—a man who grew up poor in Virginia—comes back to the south from Haiti in the 1840s to build a mansion on a hundred acres of mud in Mississippi. He gets rid of his Haitian wife, along with his first son, when he finds out she is part African. He marries the daughter of a local merchant, to get some instant middle class respectability. It’s all part of The Design, the plan he set in motion when he left rural Virginia.

The man’s sins and his broken children come back to destroy his family. In the same way slavery and racism came back to destroy the pre-Civil War way of life and made the south an apartheid for the next century and a half. Absalom turns into a pretty depressing story for all involved (And I read it the week before Christmas!)

The mystery that drives the story is, we find out years later that there’s something hidden in Thomas Sutpen’s house. It’s evil, it’s scary. But what is it?

Several years ago I was in a class with a writer who grew up in the south. I remember teasing him that he had an advantage over the rest of us. “You have all the eccentric relatives and complicated history.”

I’ll need to read more of him to judge, but I don’t think Faulkner’s work was good just because he had rich material on his home turf. He dug into why all human beings make the choices they do, how people living through the same events interpret them so differently.

And how a person’s actions inevitably ripple down the generations. Like a father passing racism down to his son. Or my mom giving me her love for stories and good writing.

Almost a week later, the poetic cadences of Faulkner’s writing are still echoing in my head. As a writer, I want to capture some of his style (though maybe not the long sentences).

Many images from the book stick with me, especially one in particular. Faulkner describes the women of the south as “ghosts” after the civil war. I picture southern belles and tough old matriarchs, wandering the dusty streets of Jefferson, Mississippi, in their faded ball gowns, powerless and poor ghosts, far from what they used to be.

As I sit with my mom, whose eyes flicker almost imperceptibly between open and closed, it’s hard not to think of her as one of those. ♥

Great post. Thank you!

Thanks, Chrissy!